On a hot, sunny Sunday in August the Tacoma Farmers Market at Ruston drew hundreds of people who browsed through and bought produce, flowers, homemade baked goods, snacks, sauces, honey, clothing, quilts, and more. Families played on the sprayground in Ruston’s Grand Plaza while others took advantage of the cool breezes coming off Commencement Bay to go for a stroll along the waterfront or a surrey ride over to Dune Peninsula Park.

Although it might be hard to picture it now, Ruston was the location for a massive copper and arsenic-producing smelter operation for almost 100 years. In fact, the town of Ruston was named in honor of William Rust, the man who ran the smelter at the start of the 20th century. Ruston and the northeast part of Tacoma were shaped by the smelter and its pollution, and the subsequent cleanup and redevelopment of the area have transformed Point Ruston into a bustling destination for folks throughout the South Sound.

History of the Tacoma smelter site

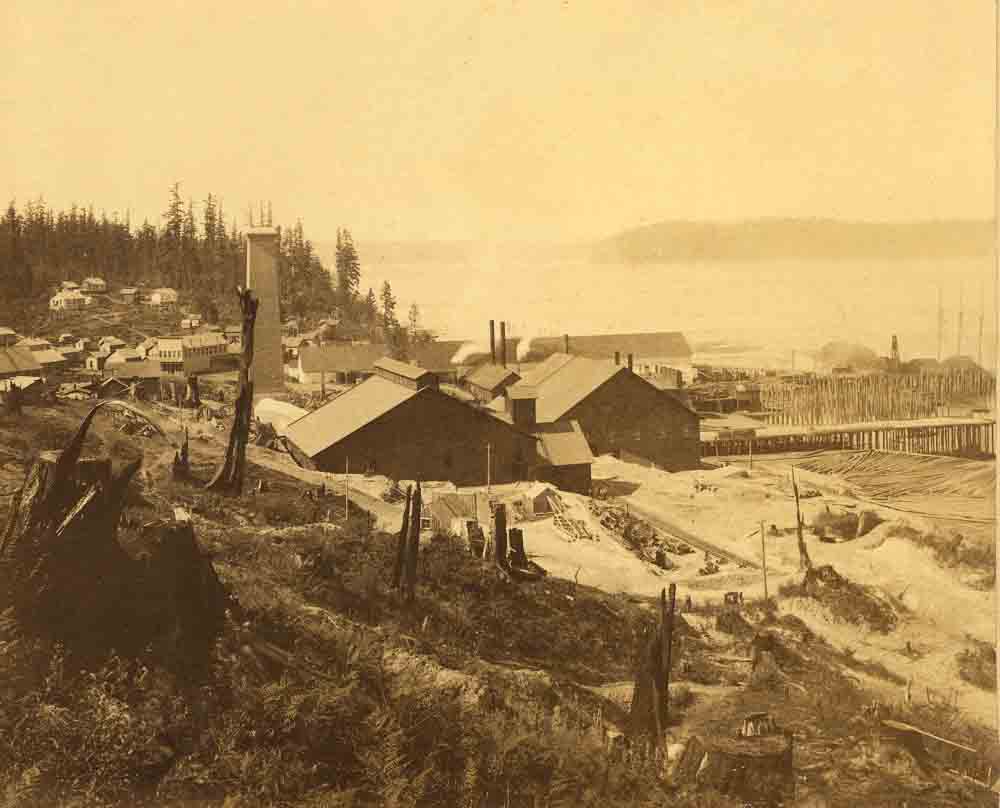

In 1889, the Tacoma Milling and Smelting Company opened on the southwest shore of Commencement Bay, where it processed the output of local lead mines. Later reorganized as the Tacoma Smelting and Refining Company under the leadership of William Rust, the company was sold in 1905 to the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO).

In 1912, ASARCO converted the Tacoma smelter to process copper exclusively. Arsenic often occurs naturally alongside precious metal ores, so the processing of those ores results in dusts and residues that contain arsenic.

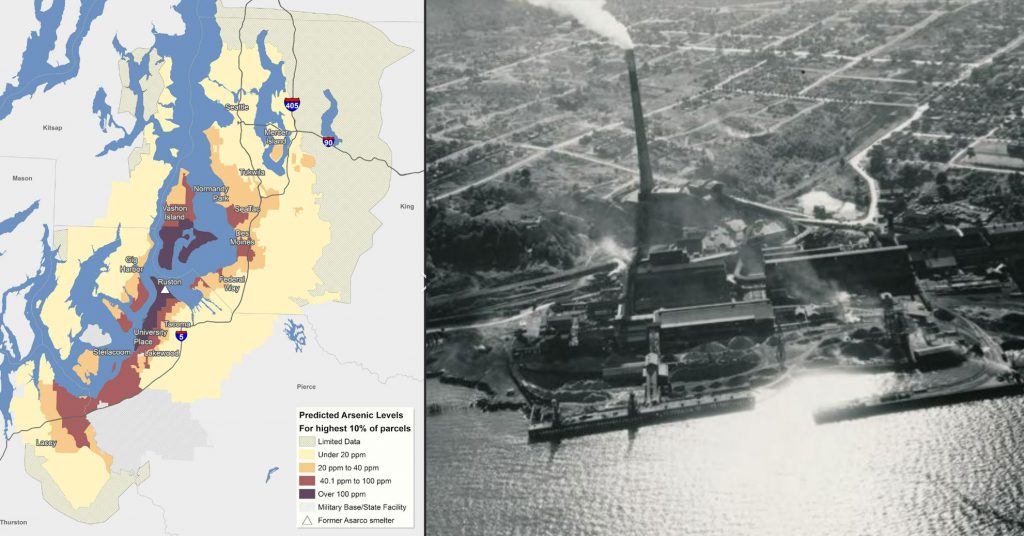

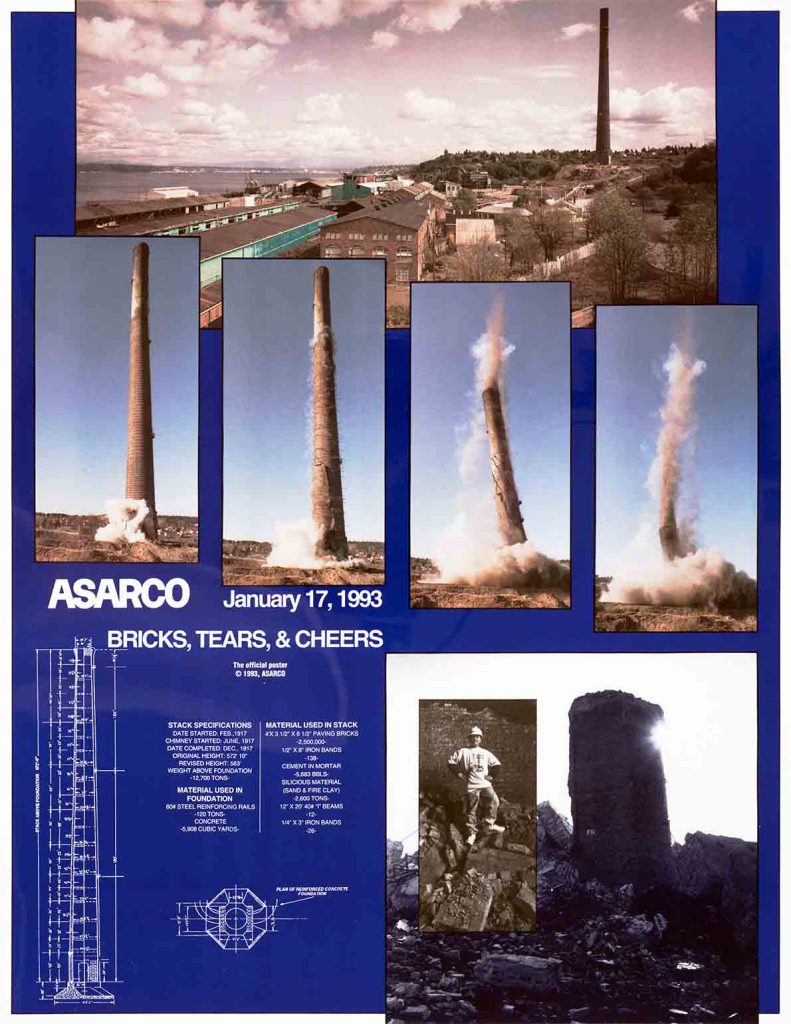

In 1918, ASARCO constructed a 573-foot smokestack, the highest in the world at that time. Higher smokestacks were thought to disperse emissions into the upper atmosphere, where they would be less harmful. However, for over 70 years, pollution from the smelter and smokestack (known as a plume) eventually settled on more than 1,000 square miles of the Puget Sound area, adding arsenic and lead to the surface soil.

The smelter eventually closed, in 1985, due to a combination of two factors: increasing awareness of the human and environmental harms of arsenic emissions (arsenic had been known as a probable carcinogen since the 1800s) and the declining price of copper in the mid-1980s.

Prior to the plant’s closing, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), in 1983, under the direction of William Ruckelshaus, had begun a process to make a regulatory decision about the smelter that also involved the wider Tacoma community. The Superfund cleanup of the smelter site and the plume, in addition to parts of Commencement Bay and the Tacoma Tideflats, has involved the EPA, the Washington State Department of Ecology (Ecology), the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department, several responsible parties, and Point Ruston, LLC.

ASARCO began demolishing the Tacoma smelter facilities in 1990 and imploded the smokestack in 1993—an event attended by more than 100,000 people, according to a January 18, 1993 story in The News Tribune (watch an unofficial video of the smokestack implosion here). The company’s cleanup of the site continued until 2005, when it declared bankruptcy.

In 2006, ASARCO’s bankruptcy settlement paid $84 million toward the cleanup of the smelter site, with $29 million going to the EPA, $50 million to Washington state, and $5 million to Metro Parks Tacoma. EPA has used those funds to continue the cleanup at the site, and Ecology has used the funds paid to the state to sample and replace contaminated soil in residential yards throughout the area of the smelter plume.

During bankruptcy, ASARCO sold the former smelter property to Point Ruston, LLC, which has redeveloped the site into a waterfront village that includes residential and commercial buildings, green space, and a path that connects to both Dune Peninsula Park and Point Defiance Park. In the settlement, Point Ruston agreed to cap the site and has been doing so concurrently with development.

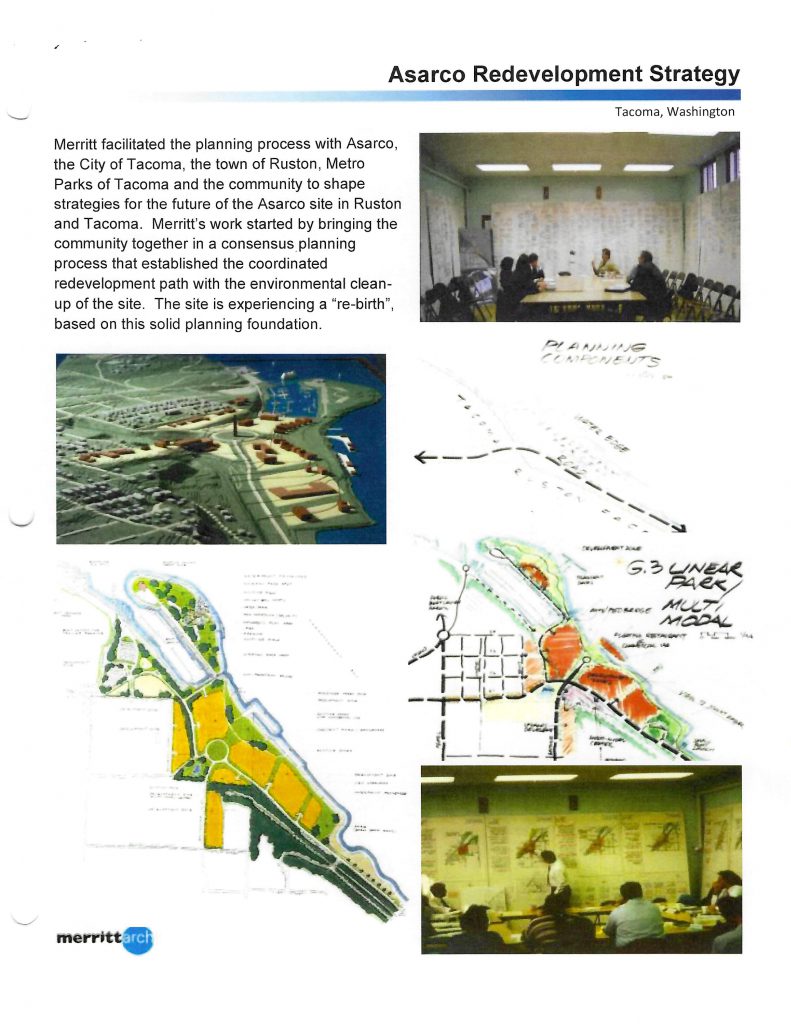

In the 1990s, when the EPA invited the community to take part in discussions to envision the future of the smelter site, Jim Merritt, FAIA, architect and principal with Merritt Arch PLLC (Merritt+Pardini at time of the project) in Tacoma, was hired by ASARCO, the City of Tacoma, the Town of Ruston, and Metro Parks Tacoma to lead the process to brainstorm ideas for the redevelopment of the smelter site. Merritt had worked on the rehabilitation of Tacoma Union Station and had experience with building consensus among diverse groups. Merritt recruited Owen Lang, a landscape architect—then with Sasaki Associates in San Francisco—to help with the process.

Merritt and his team set up at the Ruston School, then unoccupied, and used a couple old classrooms as their planning rooms. There, they held meetings with ASARCO, the City of Tacoma, the Town of Ruston, Metro Parks Tacoma, and different groups of residents. As Merritt explained, the initial meetings focused on brainstorming. “When somebody said something, made a comment, I had these five-by-eight cards, and we put it up on the wall,” he said. “We put everything up. It was an open discussion at the table.”

Reflecting on his experience, Merritt highlighted the importance of the partnerships and trust that allowed the redevelopment to move forward. “There were a lot of players involved—it’s not something that one person can take credit for. This was a huge team effort. I’m thankful we had a chance to be a part of it.” Merritt made special mention of the people who helped drive the visioning process: his colleague, Owen Lang; Tom Aldrich, then vice president for environmental affairs for ASARCO and manager of the Tacoma site; Michael Transue, mayor of the town of Ruston at the time; Karen Pickett, then project coordinator with ASARCO; the late Paul Miller, member of the Tacoma City Council; and the late Dave Nation, remediation manager with Hydrometrics.

Over the course of about six months, the group looked at alternative plans for the site and narrowed it down to a final vision. With Aldrich, Merritt presented the final plan to the ASARCO board of directors in New York, who voted to support the shared vision.

What emerged from this collaborative process was a vision of a waterfront area full of life: residences, businesses, and areas for recreation along Commencement Bay. An April 10, 1994 story in The News Tribune outlines what Tacoma and Ruston residents wanted to see:

“…a mix of office buildings, shops, and restaurants….rows of new condominiums lining the hillside above the shorefront….Imagine walking farther along the wide shorefront greenbelt that separates the office park from the water. You dodge the occasional cyclist and pass couples pushing strollers. After stopping for ice cream cones at a little stand near a dock where ships once unloaded ore, you continue toward today’s destination: the Metropolitan Park District’s stunning new 10-acre park on what used to be a barren, fenced-off slag pile.”

Thanks to community input and advocacy—and the partnership between the EPA, Ecology, and others—this vision has been fully realized. The Tacoma smelter site has been completely transformed from polluted industrial area to popular waterfront destination. Metro Parks Tacoma’s Dune Peninsula Park, constructed with the help of EPA on the location of ASARCO’s former slag pile, has won national awards for park design and is one of the most popular parks in Tacoma. Thousands of folks from around the region visit Point Ruston and the surrounding area each year to enjoy the green spaces and waterfront recreation offered there.

Point Ruston today

Many of the folks who come to visit Point Ruston do so because of its proximity to Commencement Bay and the recreational opportunities it offers. Diana Etheridge, a teacher from Marysville, came to Ruston with her friends to see Tacoma and spend some time by the water. “I love the views and I love the outdoors,” she said. “I love being able to spend time outdoors, especially in summer.”

Gary Rim, who, along with his family, came to Ruston from Puyallup for the day, said that he was born in Tacoma and loves the diversity of the area and the way people in the community support each other. He said he loves living here because of “the water accessibility, and the chance to see orcas every once in a while.”

Susie Nalivka and Steve Wachtler and their daughter live up the hill from Ruston and visit every week. “Having kids, it’s the perfect place for families,” said Susie. “It feels safe, there’s a nice bike trail, there’s the playground and the splash pad. The restaurants are nice, it’s pretty much an ideal place.”

Liv and Jason Perez and their three kids were visiting Ruston from Kent for the second time in a month. The Perezes said they’d visited Ruston to celebrate their anniversary and liked it so much that they wanted to come back with their whole family.

“What they’ve done here at the Point is build such a sense of community,” Liv said. “It’s also kind of fresh and exciting and a place where you can spend all day and enjoy so many different aspects. You can enjoy the beach, the boardwalk, this water play pad, and having the market here is genius, too, with all the different restaurants. It’s really got a little bit of everything that can appeal to everyone in your family.”

Jason added that what their family likes about Ruston is what they like about living in the Puget Sound region. “I think it’s being able to go to places like this, to the beach and then, 15 minutes later, if you wanted to, we could go on a hike, and then right after that, we could take the kayak and the paddleboard out on the lake. I think it gives our kids a sense of adventure, that they have these different opportunities to see and try different things that you wouldn’t necessarily get to do in other parts of the country.”

In thinking about what he’s seen happen over the last 30 years at the smelter site, Jim Merritt praised the process and the end result. “When I go down there now, I enjoy it,” he said. “Whenever I do design work and see the finished product, I look at the people. How are they using the space? That’s [Point Ruston LLC’s] final site plan, and I always felt they hit the mark. It’s just awesome.

“Just think, if we weren’t able to get all the players together and get this process going, what would we have? Would there still be a fence around a dilapidated site? That may happen too many times. And unfortunately, that is exactly how it could have stayed for decades. So experiencing the resulting outcome is the joy.”

Thanks to the following for their contributions to this article: Diana Etheridge, Gary Rim, Susie and Steve Nalivka, Liv and Jason Perez, Kristine Koch, Piper Peterson, Suzanne Skadowski, Rafi Ronquillo, Carolyn Huynh, Karen Pickett, and Jim Merritt.