Born and raised in Virginia, Amy Eberling’s love of the ocean began on family trips to the Assateague and Chincoteague Islands. Although she may not have realized it at the time, those experiences planted a seed that would later bloom into The Salish Sea School.

Seeing the movie “Free Willy” as a child and spending family vacations on the West Coast are when the first few leaves sprouted and the root took hold.

“Yeah, it’s embarassing to admit,” says Eberling, laughing. “But I’m (from the) ‘Free Willy’ generation. Adopting an orca in the wild when I was 8 or 9; that’s what drew us out to the West Coast, wanting to see them in the wild because of that movie. And then I spent moments on the water with the orcas and learned about the Southern Residents and their story.” As soon as she landed in Washington, she knew she’d end up there one day.

After having taught high school biology in a windowless classroom for 10 years in North Carolina, Eberling knew it was time for a change. In 2016, she, her husband, Nick, and daughter, Isla, moved to Washington State as soon as her husband’s job allowed.

“It was during my experience working with youth outside (while teaching), I was like, ‘This is where everything comes alive.’ So my dream for an outdoor school began when I was in a classroom. To provide some supplemental curriculum for students, get them off of their devices, to dive into place-based learning and really understand the natural environment around them…that was the dream.”

The inspiration behind The Salish Sea School

One of Eberling’s inspirations to open The Salish Sea School is the community of orcas known as the Southern Residents. After seeing them in her younger years, she learned all she could about them by attending conferences and participating in advocacy projects regarding the lower Snake River dams. This was in between teaching and building the school.

“The Southern Resident orcas are the endangered fish eaters,” explains Eberling. “In the Puget Sound, the general Salish Sea area, the wild salmon are declining. The orcas love Chinook salmon; I think it’s almost 90% of their diet. They will opportunistically eat other fish, but Chinook is their favorite.

“The community, their behavior—the way they cuddle; no kidding, it’s called ‘cuddle puddles,’ where they all just come together in the water. They have this culture that is unlike any other animal that I have had the opportunity to experience. Trying to help in any way is kind of what started the Salish Sea School.”

Eberling says the Southern Residents are considered a different eco-type than the ones called “transients,” now referred to as “Bigg’s orcas,” named after the scientist Dr. Mike Biggs. His research in the mid-1970s showed that these transients weren’t orcas rejected by their pods as originally believed, but were a genetically distinct group that roamed over large areas in small groups feeding on marine mammals such as sea lions, seals, and even other whales.

Another inspiration for the school is Eberling’s love of teaching. “I love teaching students about science,” she says enthusiastically. “…the miracle of a seed, a tree growing out of a seed, and how there is enough genetic information to produce that, is mind blowing!” After taking four years off to raise her daughter, Eberling realized just how much she missed the connection to students, and then came the desire to connect them to the Southern Residents.

She also knew how powerful student voices were after working with them and seeing strong youth leaders emerging around the world. “I thought it was important to provide the opportunity to say, ‘The Salish Sea School is here to lift you up if you really want to work on this issue or that issue.’” In short, to provide a platform for students whether it was through a beach clean up, planting trees along a salmon river, or writing elected officials or scheduling meetings with them.

“I was super passionate about connecting students to the Southern Residents,” says Eberling. “And when you learn more about them, you learn how the ecosystem is all connected, you learn about the wild salmon declining, and how the salmon rely on the forage fish (the small bait fish), then you learn that the bait fish need the eelgrass for protection, and the kelp…so it’s not just the orcas. The (school) curriculum continued to expand from there to include single-use plastic reduction to reducing stormwater contaminants such as not putting pesticides in your yard… The hope is to inspire them to care for the Earth, whether it’s simply not littering or something bigger.”

Eberling also wanted to create a safe space for kids of all ages and all backgrounds to gather. Having grown up in a loving and welcoming family, and being supported and encouraged by coaches in her sports endeavors, she is aware that there are many young people who lack the support of parents and friends. She wanted to create a gathering place where all would feel accepted and supported by community, and be free of judgement, even if it didn’t involve marine conservation.

Connecting young hearts and minds to nature

Eberling calls outdoor, place-based learning “an ignition of the senses.”

“When you’re outside, you smell the salty water, you can feel the kelp, you can drop a hydrophone and hear the orcas,” she explains. “That definitely hits your brain circuit differently than a book. Just like when a really emotional thing happens to us. You remember it forever.”

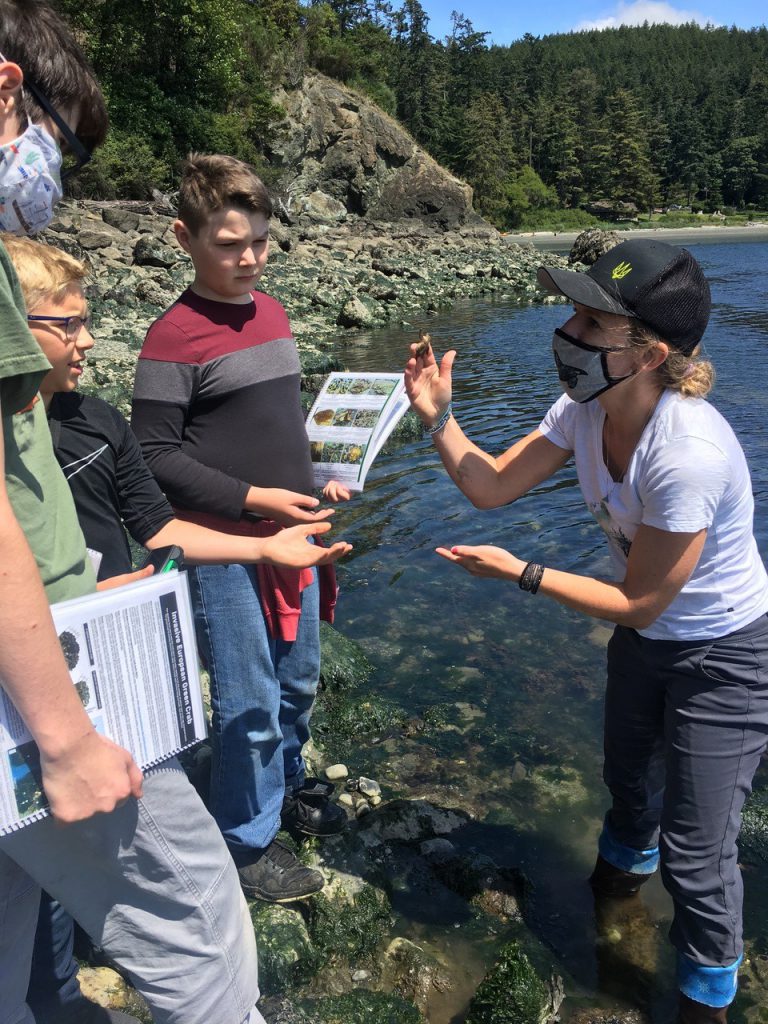

The school’s seasonal programs accommodate youths from kindergarten to 12th grade and older on or near the water. All students engage in hands-on, experiential-based learning.

Shoreline Exploration Adventures (S.E.A.) is a year-round, land-based, after-school program for kindergarten to fifth-grade students. Eberling describes it as “the classroom right outside their doorstep.” On these shoreline outings, kids explore the beaches, learn about eelgrass, encounter sea stars, shore crabs, marine birds, and whatever else happens to show up. The staff is there to explain what they’re seeing while instilling a sense of wonder and excitement in order to create a future advocate for marine life and the environment. It creates a connection to nature.

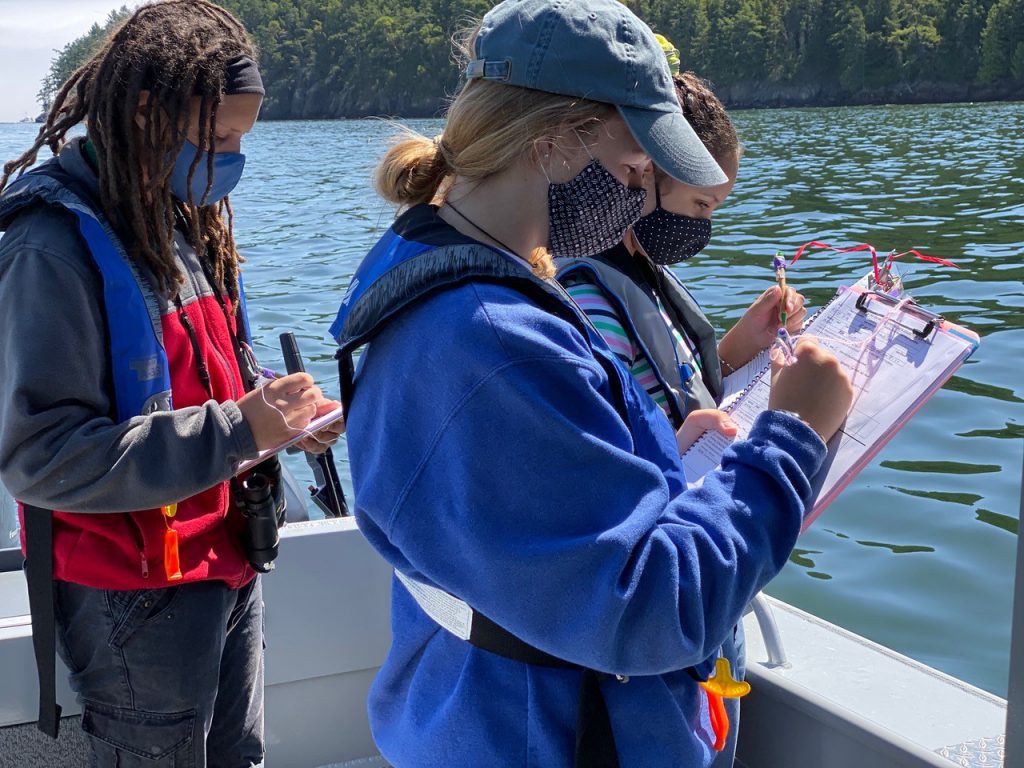

Guardians of the Sea (G.O.S.) is a summer boat-based program for 11-13 and 14-17 year olds focusing on marine birds, seals, porpoises, baleen whales, and orcas, depending on what’s on the water.

“Trevor, a second teacher and deckhand, is an intern for an organization that’s attempting to photo ID harbor porpoise,” says Eberling. “The students get to see him take pictures and do data entry. Asking the question, ‘Why?’ helps them to think critically. ‘What is a research project? What is a data sheet? Why do you need to record the tide, sun, and moon phase on the data sheet?’” These are important questions for impressionable young minds.

Two elementary summer camps have launched as well, Puffin Protectors and Southern Resident Superheroes. Both camps include fun games, forest-to-shore hiking adventures, tidepool explorations, art projects, a trip to a local island, and outdoor lessons about two iconic and endangered species that rely on a healthy Salish Sea—tufted puffins and Southern Resident orcas.

“One student is interested in marine debris, so she’s going to help lead the local marine debris survey where we’ll ask people to adopt a beach, and survey it once a month to see the rate of debris accumulation.”

— Amy Eberling

In January 2022, a new program will begin: Student Training as Research Scientists (STaRS). STaRS is a year-long marine science field training program, culminating in a project presentation of the research experience. It is for the students extra passionate about pursuing a career in marine science or conservation. Each student will participate in inquiry-based virtual lessons and in-person field work with an assigned research scientist from a local organization for one year. “I’m super excited for this program to begin!” shares Eberling. “These students are going to experience a full season of data collection, not just four days like in our Guardians program.”

The goals are to stimulate interest in a future career in the field of marine conservation science, recruit and train the next generation of marine conservation scientists, develop student comfort in an academic and professional setting, as well as provide resources that can ensure higher education success, and provide the opportunity for field research and data collection experience in marine science. There are multiple projects STaRS students can choose from: marine debris STaRS, forage fish STaRS, Bigg’s orca STaRS, and stormwater STaRS to name a few.

There’s also the Student Leadership Team that meets monthly. Eberling supports each student’s focus by personally mentoring them on whatever environmental subject they’re interested in pursuing.

“One student is interested in marine debris, so she’s going to help lead the local marine debris survey where we’ll ask people to adopt a beach, and survey it once a month to see the rate of debris accumulation,” says Eberling. “Another student is very passionate about orcas, so she’s going to do an orca presentation later this month to teach other people about the Southern Residents. It goes back to empowering these students and giving them opportunities to be leaders in marine conservation, which is our overall mission.”

On Orca Recovery Day this year, the student leaders led a virtual Summit for the Southern Resident orcas that included student-led sessions on the Southern Resident orcas and breaching the lower Snake River dams and expert sessions from Gracie Ermi of Allen Institute and Dr. Deborah Giles of Conservation Canines.

Art classes are also part of the curriculum as the school celebrates art as an incredibly effective form of expression and learning and as unique messaging to elevate marine conservation.

The school has also launched adult programs and had its first successful outings this past year, with adult program tuition going back to support the student programs by providing scholarships.

Youth perspective

With an interest in environmental science, 16-year-old Kaia Olson is part of The Salish Sea School’s Student Leadership Team. Her focus is marine debris and the lower four Snake River dams.

She learned about The Salish Sea School last year at a virtual Youth Earth Summit hosted by Padilla Bay Reserve. After making her own presentation about the connection between COVID-19 and plastic pollution, she became interested in some of the issues specific to the Salish Sea after hearing Eberling speak about its ecosystem and climate change.

“I love how The Salish Sea School helps fill in the gaps of science education,” shares Olson. “Young people like me will be, and are, taking on some of the greatest environmental challenges of our time, and we need an education that raises us to be the next generation of Earth stewards. The Salish Sea School programs encourage this invaluable connection to the Earth in many forms, and for students from all walks of life.”

Olson has many concerns about the world, but the most important one is that she feels people aren’t concerned enough, that we don’t understand that the “abstract environment” is the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the Earth on which we walk.

“I think we’ve created an illusion that we exist outside of nature,” she says. “But in order to address climate change, we must renew our connection with nature and realize that an environmental crisis is synonymous with a humanitarian crisis.”

Her advice to her fellow youths? “I would advise young people that anything they can do does make a difference,” says Olson. “Standing on the shoulders of those before us, this environmental movement needs to be propelled by youth because we have the greatest stake in the outcome. Our generation is the last defense the Earth has. And although I know how bleak the future can seem sometimes, I also know that we have the ability to change the world.”

The Salish Sea

Marine biologist Bert Webber of Bellingham, Washington, first used the term “Salish Sea” in 1988 to raise consciousness of this unique body of water and its vibrant ecosystems.

The Strait of Georgia carries saltwater down from the north; the Strait of Juan de Fuca brings saltwater from the Pacific Ocean in the west; and Puget Sound sits to the south. Freshwater coming from numerous rivers mixing with the saltwater has created a unique salinity that changes with the ocean currents and discharge from rivers. As a result, the Salish Sea is recognized as a single estuarine system providing critical habitat for an abundance of fish, marine mammals, invertebrates, shorebirds, and marine plants.

For the Coast Salish peoples, the Salish Sea is the basis of their way of life, as well as an important food resource. The Samish are part of the Coast Salish culture and the Samish Indian Nation has its headquarters on Fidalgo Island. With its canoe culture, the Samish traditionally traveled, hunted, and fished in the Salish Sea, and Chinook salmon was, and still is, a critical food source.

Issues affecting the Salish Sea and its inhabitants are climate change and human-caused pollution. Climate change greatly affects marine water quality and the marine food web. Examples of the latter include single-use plastics, microplastics, Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs) that refer to man-made chemicals, pollutants in stormwater runoff, and more.

Eberling and other boaters, who share their findings with each other, have also found balloons, especially mylar balloons, floating on the water.

“The Southern Residents have three pods—J, K, and L pods—and they all have different calls. Hearing the students’ reactions as they listen and try to understand what they’re saying…it’s really, really magical.”

— Amy Eberling

But the biggest issue, says Eberling, is wild salmon. Not only are Chinook salmon—a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act—a favorite of anglers and commercial fishermen and orcas, their guaranteed availability is written into the treaties between Pacific Northwest tribes and the federal government.

Environmental Protection Agency findings reflect a 60% reduction in Chinook salmon since tracking began in 1984. And the average age and size of returning salmon is changing as well, with fish maturing and spawning at younger ages. Larger-sized fish are less common as well.

In addition to the salmon, the Southern Resident orcas are also threatened. According to the Puget Sound Vital Signs, Southern Resident orcas are being subjected to underwater noise and disturbance caused by commercial and recreational vessels in the Salish Sea. They are also having to stay for longer periods outside the area to access prey since the Chinook salmon population is declining.

According to Eberling, who knows these waters and its inhabitants well, Southern Resident orcas used to historically stay in Salish Sea waters from April through September. Now they barely visit during summer, just sporadically, for no more than two to three weeks.

One of her favorite experiences is being with the students out on the boat and listening to the Southern Residents through a hydrophone in the water. “The Southern Residents have three pods—J, K, and L pods—and they all have different calls. Hearing the students’ reactions as they listen and try to understand what they’re saying…it’s really, really magical.”

On making a difference

The opportunity to connect all youths with the natural world is what keeps Eberling going.

The Salish Sea School is scheduled to host a group of 25 Latinx students in the Guardianes del mar (Guardians of the Sea) program, coordinated through Washington State’s GEAR UP program. It’s just one of the opportunities that Eberling was hoping for when she opened the school, introducing all students to the sea. She truly believes that experiencing the Salish Sea for the first time will always be remembered and is the first step towards a desire to protecting it.

“My greatest joy is bringing these kids on the water and teaching them about organisms that depend on their choices and their actions,” says Eberling with a wide smile. “I love, love, love teaching students about this marine life. It’s almost otherworldly to me, the oceans. Some people want to explore the solar systems and I want to explore the oceans because there’s still so little known about it.

“I feel really lucky to have found something that lights me up so much that I feel is a small gift to give back to the world…to make the Earth a little bit better.

“You try so hard to think about this one special life you have. How can you make a difference? My hope is that this school echoes into the future with the student leaders that participate in our programs…really, truly empowering them to continue making this world a better place.”

Visit www.thesalishseaschool.org for information on programs and opportunities.