Did you know that some kelp species are among the largest of all seaweeds? And did you know Washington state is home to 22 species of kelp, which means there are more kelp species here than anywhere in the world except for Japan? Or that kelp not only provides a home for many species of fish and other wildlife, but also forms the basis of their diets as well? Did you know that massive kelp forests, stretching around the North Pacific from Asia to the Americas, may have helped the first people migrate to the Americas by boat thousands of years ago?

And did you know that large kelp beds have vanished from areas near Australia and northern California, and that Puget Sound has been losing its kelp for the last forty years?

The good news is that many partners, working side by side, have come up with a plan to save kelp in Puget Sound. The Puget Sound Kelp Conservation and Recovery Plan (the Kelp Plan) outlines six goals to help protect and restore kelp species.

“Kelp and eelgrass are the bottom of the food chain. If you take that away, you dramatically shift the landscape, and it’s hard to predict what changes that would mean for us as people.”

–Toby McLeod

Why is Puget Sound losing its kelp?

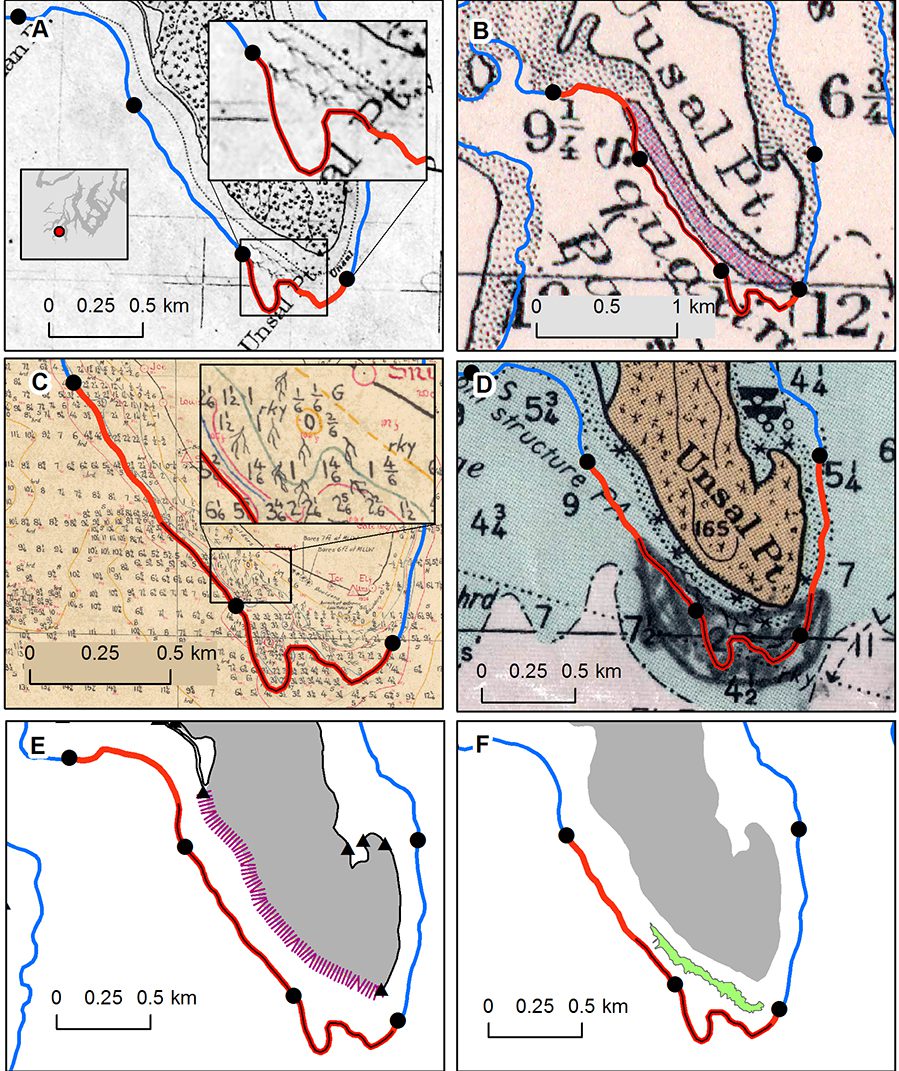

Up until the 1970s, bull kelp and other types of kelp thrived in Puget Sound. From maps and surveys from the 1870s, the 1930s, and later, we know that kelp beds were bigger and covered a larger area of Puget Sound than they do now.

“Where we used to see a lot of kelp, we don’t see it anymore, other than the outlying areas.”

–Ron Garner

Tom Mumford, head of Marine Agronomics and retired natural resource scientist with the Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR), saw many thriving kelp beds disappear after the early 1980s. Mumford expressed concern to Helen Berry, a natural resource scientist with DNR, and they began doing surveys throughout Puget Sound and collecting historical data.

Over the last 10 years, a growing number of other people also noticed that Puget Sound was losing its kelp. The Suquamish Tribe noted the loss of kelp near Doe-kag-wats, a beach on Suquamish land, and contacted Puget Sound Restoration Fund (PSRF) to partner on restoring the kelp bed. Recently, the Samish Indian Nation did a study on the bull kelp beds in the San Juan Islands and found a 305-acre loss of kelp beds from 2006 to 2016, a 36 percent decline in one decade.

Berry explained that she’s heard from many people about the loss of kelp when she’s out doing field work, but mostly from anglers and fishermen. Ron Garner, president of Puget Sound Anglers, said that he and other anglers talk about the loss of kelp often. “Where we used to see a lot of kelp, we don’t see it anymore, other than the outlying areas.”

One of the goals listed in the Kelp Plan is to figure out why kelp is no longer thriving in Puget Sound and what factors might be causing its decline. Warmer water may be one factor that’s harming kelp, but more research is needed.

“We think temperature is and will continue to be a problem,” said Mumford. In its life cycle, kelp goes through phases where it is microscopic in size, and Mumford explained that it might be in these phases that kelp is most at risk to warm water.

The importance of kelp

Like eelgrass, kelp gives fish, invertebrates, and other species a habitat in which to live. Floating species of kelp, like bull kelp, form a canopy on the water’s surface, while other types of kelp thrive underwater or cover the sea floor. Kelp forests allow young fish to mature in safety and provide habitat for the invertebrate species that support young salmon, rockfish, and surfperch and other forage fish.

Kelp is also a food source in the Puget Sound food web. Many marine creatures consume kelp firsthand or eat the small pieces that the kelp sheds, and others, like salmon, sculpin, surfperch, and gunnel, consume the creatures that eat kelp.

Paul Chittaro, research fish biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), looked at the carbon and nitrogen isotopes in the tissues of fish and invertebrates to see how much of their diets come from kelp. Chittaro found that, for many of the species that use kelp beds as a habitat, much of their energy, and what they incorporate into their bodies, comes from kelp. “Kelp has this importance in the food web, it’s a supporting resource for rockfish and other species,” said Chittaro. Since kelp supports salmon, it also supports species in the food web that prey on salmon, like orcas, marine mammals, and birds.

“…you could park your canoe on this kelp and just fish. Hook and line off the kelp bed, and you could stay out there—if you had enough water—for as long as your water would last.” — Toby McLeod

Kelp is crucial for people as well. A section of the Kelp Plan focuses on the cultural importance and uses of kelp for Pacific Northwest tribes. Nicole Naar, postdoctoral research associate with NOAA, compiled this section of the plan in consultation with tribes throughout the region. As the section outlines, kelp features in many of the story and myth traditions of Pacific Northwest tribes. Kelp has also been used as part of fishing, hunting, and cooking practices for Coast Salish peoples.

Toby McLeod, Samish citizen and field technician with the Samish Indian Nation Department of Natural Resources, explained that his father said the fishermen before his generation—and before motorboats—used big floating kelp beds to help them fish. “Kelp beds in the Puget Sound would break off into half-acre to acre floating islands,” said McLeod. “And you could park your canoe on this kelp and just fish. Hook and line off the kelp bed, and you could stay out there—if you had enough water—for as long as your water would last.”

Kelp forms a key part of the Puget Sound ecosystem. As McLeod said, “Kelp and eelgrass are the bottom of the food chain. If you take that away, you dramatically shift the landscape, and it’s hard to predict what changes that would mean for us as people.”

The Kelp Plan

The Kelp Plan grew out of a plan to recover rockfish in Puget Sound. Dan Tonnes, Washington and Oregon aquaculture coordinator with NOAA, said that when he worked with anglers on rockfish recovery projects, they often expressed alarm about the loss of bull kelp. Tonnes and others at NOAA started talking to their partners at DNR and the Northwest Straits Commission, and found they were hearing similar concerns. “It turns out there’s a big community of people who have seen a decline in kelp in their lifetimes, and that got us started trying to figure out what to do about it,” Tonnes said.

Following those early conversations, a group of partners including several tribes, NOAA, DNR, Northwest Straits Commission, Northwest Straits Foundation, Puget Sound Restoration Fund, Marine Agronomics, and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife decided to make a work plan to learn about the decline of bull kelp in Puget Sound and conserve and recover all the kelp species.

“There are so many organizations and people that put in a lot of time to make this what it is because they care about kelp a lot.” –Dana Oster

With financial support from NOAA and project management from Northwest Straits Commission, scientists and planners turned theory to action by creating a work plan that would inform the future Kelp Plan. Max Calloway, a natural resource scientist with DNR (who was working with Puget Sound Restoration Fund at the time), and Dana Oster, marine program manager with the Northwest Straits Commission, are two of the main authors of the Kelp Plan. For the first phase of the plan, Calloway and Oster gathered knowledge about kelp to figure out what still needed to be researched. For the second phase, Calloway and Oster said the plan grew through team work. “A lot of people came together at the right time,” said Oster. “There are so many organizations and people that put in a lot of time to make this what it is because they care about kelp a lot.”

Calloway explained that the more people learned about the loss of kelp, the more they felt the Kelp Plan had an urgent purpose. “Momentum got going,” he said. “And people started to see how little we knew in our region and how important this ecosystem is for the whole health of Puget Sound.”

All the partners involved with the Kelp Plan have big hopes for the plan and its six goals. As Oster said, “We’ve built enthusiasm and awareness, but it’s going to take everybody who cares about kelp to build support for the actions in the plan.” Calloway explained that it should be easy to make the case for kelp conservation and recovery. “When you think about it, what’s good for kelp is good for Puget Sound,” he said.

What happens next

“It’s incredible how much interest and concern there is about kelp right now compared to two years ago.” – Tom Mumford

There are protections for eelgrass in Puget Sound, and, as Berry explained, those same laws cover kelp too, though not many people know that. “Since we already have the regulatory protections in place, the next step is to increase implementation of existing regulations,” Berry said. “And DNR is working on increasing awareness through its aquatic land management work.”

Berry and Calloway stress how crucial it is to conserve kelp and save the beds that we have, especially while trying to address climate change and warming oceans. As the Kelp Plan mentions, there’s no state policy or local action “that can ‘lower the thermostat’ on Puget Sound waters.” But there are actions we can take to reduce the impacts of climate change on kelp, such as creating protected kelp areas and improving water quality in Puget Sound.

On the recovery front, Puget Sound Restoration Fund (PSRF) has established a kelp lab at NOAA’s Manchester Research Station to grow kelp that can be planted at restoration sites. Betsy Peabody, executive director of PSRF, said, “We’ve been experimenting with seeding techniques, and we’re producing various life stages that can be planted at sites to re-establish kelp forests.” PSRF is already conducting experimental kelp planting with NOAA and Port of Seattle, and is launching an underwater kelp monitoring program. Next on the agenda is working with scientists at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee to develop a kelp germplasm bank from seed stocks collected throughout Puget Sound, to use for cultivation, genetic analysis, and restoration projects.

The people involved in the creation of the Kelp Plan hope that Puget Sound kelp can be recovered. There’s a sense of momentum building around the effort to save kelp, not only here, but around the globe. “Everywhere in the world has exploded with concern, with information, with things similar to what we’re doing here,” Mumford said. “It’s incredible how much interest and concern there is about kelp right now compared to two years ago. It’s an order of magnitude more.”

The loss of kelp in Puget Sound demands a regional response. The Kelp Plan lays out six goals and related actions for protecting and restoring kelp forests. It outlines the need for collaboration, better communication between researchers and managers, and increased funding for research, monitoring, education, implementation, and enforcement. It will take the shared effort of many people and organizations to achieve the Kelp Plan’s goals, but with cooperation and collective action, all 22 kelp species will continue to flourish in Washington state waters.

Featured photo: Photo of bull kelp floating in the water. Photo credit: Adam Obaza, biologist, Paua Marine Research Group.

More information

The Northwest Straits Commission has published the Kelp Plan and its two appendices, which contain an overview of scientific knowledge about Puget Sound kelp and an overview of the cultural importance and uses of kelp for Pacific Northwest tribes. As the Northwest Straits Commission states on its site, “Kelp conservation and recovery is an ongoing effort.” Partners who are interested in joining in the vision outlined in the Kelp Plan or who are interested in contributing to recovery should contact the Northwest Straits Commission.

The Puget Sound Institute’s Encyclopedia of Puget Sound contains a number of articles about the decline of kelp in Puget Sound and research related to kelp restoration.

Vital Sign connections

The Vital Signs measure the health of Puget Sound and progress toward its recovery.

Starting in January 2022, floating kelp canopy area will be monitored and reported upon as part of the revised Puget Sound Vital Signs. The floating kelp canopy area indicator will inform the new Beaches and Marine Vegetation Vital Sign, which will also include indicators about feeder bluffs in functional condition, extent of forest cover that exists in nearshore marine or riparian areas, and the area of eelgrass, along with short- and long-term eelgrass site status.

Chinook Salmon

Kelp species in Puget Sound provide habitat for juvenile salmon. Kelp also forms a significant portion of the diets of the small fish and invertebrates that juvenile salmon prey on. Protecting and restoring kelp species in Puget Sound contributes to the recovery of Chinook salmon and other salmon species.

Marine Water Quality

Marine water quality refers to many aspects of water such as temperature, salinity, oxygen, nutrient levels, algae biomass, and pH. The Marine Water Quality Vital Sign tells us about the combined impacts of global and local change and human-caused stresses on Puget Sound marine waters. Marine water quality affects kelp species throughout Puget Sound. The Kelp Plan outlines the research that’s needed to understand these effects for the protection and restoration of kelp species.

Cultural Wellbeing

Kelp is culturally important for Pacific Northwest tribes. Kelp features in many of the story traditions of Coast Salish peoples and has been used as part of fishing, hunting, and cooking practices. Continuing practices and traditions is critical to human wellbeing. Conserving and restoring Puget Sound kelp ensures that diverse cultural practices and traditions will continue.

Outdoor Activity

Kelp beds provide habitat for fish species, like salmon or rockfish, that recreational anglers and other fishermen prize. Fishing—for recreation or as an occupation—depends on a healthy ecosystem. The Kelp Plan lays out the steps required to preserve kelp as a key habitat for important fish species.