This episode of Making Waves Conversations features an interview between Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet, executive director of the Puget Sound Partnership, and Nora Nickum, senior ocean policy manager at the Seattle Aquarium and author of books and magazine articles for kids. In the interview, Laura and Nora discuss Nora’s new book, “Superpod: Saving the Endangered Orcas of the Pacific Northwest;” orca recovery; and what it takes to make scientific information accessible for all readers. This conversation was recorded at the Seattle Aquarium on April 27, 2023.

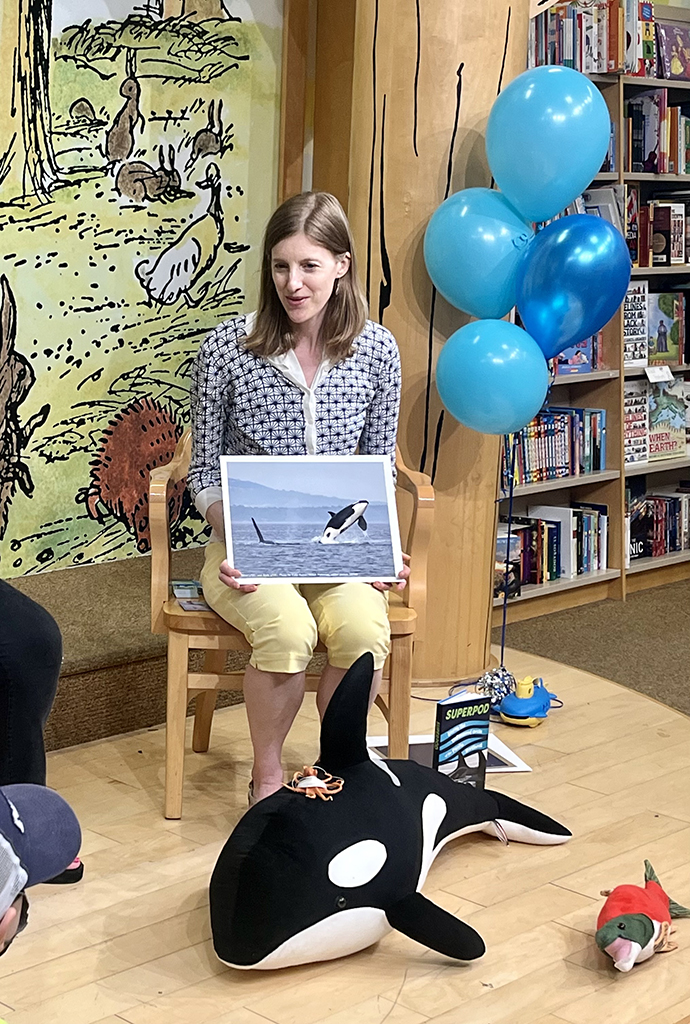

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: My name is Laura Blackmore and I’m the executive director of the Puget Sound Partnership, the state agency formed to lead our region’s collective effort to protect and restore Puget Sound. Our online magazine, Making Waves, and associated podcast, Making Waves Conversations, both feature stories about the people working to protect and recover Puget Sound. For this episode of Making Waves Conversations, I’m speaking with Nora Nickum, the senior ocean policy manager at the Seattle Aquarium. Nora is also the author of books and magazine articles for kids. Her middle grade non-fiction book, Superpod: Saving the Endangered Orcas of the Pacific Northwest, published by Chicago Review Press in April 2023, introduces readers to the playful and beloved Southern Resident orcas and the people working to save them using everything from medicine and laws to drones and dogs. Nora, thank you so much for joining us today. For our conversation, we’re going to talk about your book, your writing process, and orca recovery.

Nora Nickum: Thank you for having me, Laura.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: So my first question for you is how did you decide to write Superpod? What sparked the idea for you?

Nora Nickum: So I started writing for kids a few years ago. I have a young daughter and I also just love seeing the kids visiting here at the Seattle Aquarium who are so excited about marine life, and hearing the questions they ask, and seeing what sparks their curiosity. So I was particularly interested in writing for kids and doing both fiction and non-fiction, and ocean animals tend to feature in all my writing because of working at the Seattle Aquarium and also just a childhood growing up in the Puget Sound area, spending time checking out tide pools and looking for wildlife. This particular book came about–I think part of the inspiration came in 2018. I was on San Juan Island, and I was on shore looking out, and there were orcas nearby, and I saw some people in a boat getting a little too close, I thought, to an orca with a very long pole.

And I was trying to figure out what was going on. I thought maybe they were documentary filmmakers trying to get a good shot, and I was really worried. It wasn’t until a couple of days later that I saw in the newspaper the story about Scarlet, J50, and I realized that the people in that boat had a petri dish on a long pole and they were collecting a breath sample.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: Oh, wow.

Nora Nickum: Because Scarlet was not doing very well. She was having trouble keeping up with her family. She was underweight, and everyone was trying to figure out what’s going on, if there was anything they could do to help. So that breath sample was an important part of figuring that out. And I got really interested in the challenges of helping these whales in non-invasive ways, letting her stay with her family in the wild and roam free, but realizing that young females are also the future of the population.

And that was at the same time that the Orca Task Force was happening, as you know, and kind of seeing how stories like that really helped add more momentum to that process and make it feel urgent and real. And feeling like that kind of story really can inspire both empathy and action and thinking about how else can story do that. That particular story didn’t have a happy ending, but that became part of the book surrounded by lots of chapters that are much more hopeful and show people working to help these whales in other interesting and innovative ways.

“That kind of story really can inspire both empathy and action.” – Nora Nickum

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: And how cool that you saw that, that was–

Nora Nickum: I know.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: –interesting.

Nora Nickum: Yeah.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: It was in the right place at the right time.

Nora Nickum: …at the right time.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: Land-based whale watching: a good thing. Yes. All right. Well, what was the process like writing this book and how long did it take you to write it?

Nora Nickum: Yeah, it was about two years from start to finish from sending that proposal off to a publisher and then having the book in my hands. So several months researching and interviewing amazing scientists and advocates and educators and trying to bring their words into the story and trying to collect lots of photos. And so it was a while, but it was fun. I did a lot of it in the early mornings before my Seattle Aquarium job.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: I was going to say, was this part of your job or was that something separate?

Nora Nickum: It’s not part of my job.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: All right, good to know. And what did you learn in the course of writing the book that you found most surprising or most fascinating, and what was the best part of the experience of working on the book?

Nora Nickum: Yeah, in terms of most interesting, I was really intrigued by the question of why orcas breach, and I thought that would be a really fun thing to talk about with kids.

So I visited Lime Kiln State Park where Dr. Robert Otis has been studying these whales and their behavior for three decades. Patiently waiting and talking to people about whales until the orcas swim by and they can write down what they’re doing and what else is happening around them. And so, I was kind of asking him why does he think they breach and what has he found from his data so far? And he was telling me things like, they seem to breach more when there are two or three pods together rather than just one. So it’s probably sometimes tied to socializing and play. They also tend to breach more when they’re waking up from sleeping. And I thought that was really cool. It’s kind of like stretching when you get out bed. They also breach more when there are more boats around and probably because it helps them communicate with each other and maybe even alert the boats, “Hey, watch out. We’re here.” And the splash after a breach is loud and visible, so it can be a way for them to communicate when maybe the calls are not getting through the noise.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: Oh, wow.

Nora Nickum: So those are just some of the reasons. I like to think about how it’s still kind of mysterious and how it depends on context. Just like when humans wave, we might be waving for a lot of different reasons. It might be a greeting, it might be trying to get someone’s attention, it might be swatting away a mosquito. I think it’s probably similar that the orcas have a lot of different reasons why they do that, and it depends on the context. So that was a particularly fun thing to explore. I think another one that was interesting to explore—because I get the question so often in presentations—people a lot of the time ask, “Okay, the Southern Residents are having a hard time finding enough salmon. The other orcas that eat marine mammals are doing great. Why don’t the Southern Residents switch?”

And I feel like I’d had answers to that before, but being able to dig into it more and ask more experts questions and read the research helped me kind of understand better that these orcas are all specialists. So around the world, different orca populations focus on different things, and that has been really advantageous for them as long as the ecosystem is all in balance. Some of them in Iceland, they eat herring and offshore orcas eat sharks and Southern Residents eat salmon. And so when you specialize, you can get really good at that one thing and that can help you thrive. But if that one thing is no longer abundant, that can be a problem. And the skills that they’ve used, that they’ve honed for millennia to be really good at catching that one kind of prey, do not translate well to anything else. So that’s one thing. If you are gregarious and loud and communicative, like the Southern Residents are, you’re not going to be able to catch a marine mammal that can hear all of that.

But also, just the process of sharing prey with their young—so when an orca catches a salmon, they break it into pieces, they share it with their family members, that’s how they tell the young ones what food is. And so if a parent never shares anything else with the young ones, it’s not going to occur to them that something else could be food. So kind of thinking through that was really interesting, made me feel maybe better prepared to answer those questions when I get them now, because they come up a lot.

“[W]hen an orca catches a salmon, they break it into pieces, they share it with their family members, that’s how they tell the young ones what food is. And so if a parent never shares anything else with the young ones, it’s not going to occur to them that something else could be food.” – Nora Nickum

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: I’m sure. And speaking of which, there is some complex scientific information in the book about orcas and their ecosystem that you do a really good job of communicating in an accessible way. So how hard was it to translate some of that technical information in a way that would be both understandable and interesting for younger readers or readers who simply are unfamiliar with the science?

Nora Nickum: I would say that was maybe the most fun part for me.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: Oh, cool.

Nora Nickum: I really like that. I think also there’s a parallel to the work I do in my day job with legislators and decision makers. You need to be able to translate science in digestible and interesting ways. And I’m not dumbing it down for kids—I don’t dumb it down for legislators—but you need to be concise and try and find ways to make it relatable. So I like trying to find analogies for kids to put in the book. For example, we know that when the orcas are surrounded by boats, and there’s a lot of noise, that they have to speak up. They amplify the volume of their calls. And I was saying that’s kind of like kids in a really loud cafeteria, if you see your friend at the other end of the table, you’re going to have to shout. And if you have to do that all the time, it might get kind of tiring. And it does take the orcas more energy to do that. It’s a solution they’ve found, but it’s not one that would be good for them to have to use all the time.

“…I have a chapter where I kind of lay out for kids, let’s say there was a new kind of whale and you were trying to figure out what it ate. What approaches do scientists use to try and figure that out?” – Nora Nickum

I also thought it was really interesting to think about how Western scientists didn’t figure out what these orcas’ diet was until actually fairly recently. I mean, it might seem like a long time ago for kids who were reading this, it was like the ’80s—I mean, to me that seems recent. But so it wasn’t until the ’80s that they figured out the Southern Residents eat fish, while other orcas in the region eat other things. Right now, it feels really obvious to us, but it wasn’t always. And then it wasn’t until the 1990s, they realized it was mostly salmon.

And so I have a chapter where I kind of lay out for kids, let’s say there was a new kind of whale and you were trying to figure out what it ate. What approaches do scientists use to try and figure that out? So you can watch from a boat or from shore and see if they leave any scraps of food behind and see what it is. You can collect their scat and see what’s in their scat. You can, if you happen to find a dead whale, which would be sad, you can do a necropsy and see what’s in its stomach. And you have to do a lot of those different things in order to figure out what do they eat. It’s not necessarily obvious, especially when they spend so much of their lives underwater. There’s a lot we don’t know about what goes on.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: In the book, you weave together information about the orcas and your own personal perspective in a way that’s compelling and keeps the focus on Southern Residents and the people who are doing the work of orca recovery. Was it hard to decide how much of yourself to put into the book?

Nora Nickum: It was, I didn’t want to write a lot about myself. I really wanted to showcase all the different people who are working to help these whales and learn about them, and the title Superpod kind of comes from that. Superpod as the name of the big family reunion that happens when J, K, and L pods get together, but also all the people that are working to help them in so many other ways, it’s kind of a superpod. And I really wanted to showcase all of that. But I did want kids to realize that you don’t have to be a scientist to help endangered species.

Science is awesome, and I hope kids will feel that way after reading this book because there’s a lot of scientists in this book who do really cool things. But if you’re not drawn to that, there are a lot of other ways you can help. And I personally didn’t go the science route. I’m in policy advocacy, which is an important way to help endangered species in the environment by speaking up for change and trying to get big-scale change to happen. And there are also educators and artists and others in the book, so I want kids to see a lot of different potential futures that they could pursue if animals and conservation is something they care about. And then I also wanted to share some stories of watching the whales from shore because those have been personally really meaningful, life-changing experiences that helped inspire me to do this work and write this book.

“Superpod as the name of the big family reunion that happens when J, K, and L Pods get together, but also all the people that are working to help them in so many other ways, it’s kind of a superpod.” – Nora Nickum

I also work on policy to encourage shore-based viewing and giving the orcas plenty of space on the water, and I just want to share that you can have really magical experiences watching them from shore, you don’t have to be in a boat. It’s a little bit more unpredictable, but I feel like that adds extra magic when it does happen.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: What would you like your readers to take away from your book when they’re done reading?

Nora Nickum: I would like readers to know these whales, these 73 Southern Resident orcas as individuals who have grandmothers, they have youngsters, they stay together for life, they have names, they make best friends as recent research from the Center for Whale Research shows. And that humans are not so different from these whales. We can see ourselves in them. We can relate to them and have empathy because we also make friends, we’re also close to family, we share food, we grieve when we lose someone. So I think helping readers kind of build that connection and that empathy, and then hopefully want to do something to help. And wanting readers of any age to feel like there are things they can do today to help these whales. It doesn’t have to be their career, but there are things that can be done now. But for kids, there might also be future careers that are really exciting to think about from science to education to advocacy.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: Superpod is both engaging and informative, and the book has a lot to offer for readers of any age, even though it’s marketed to younger readers. Did you write the book so that it would be interesting for any type of reader? Was that on your mind?

Nora Nickum: That was on my mind. I definitely have not written down to kids. Kids are really smart. But I hope that also means that older teens and adults will find this interesting and engaging and not overly simplified. I think all the information is in there. I just tried to write it in a really conversational, storytelling kind of way. Not dry non-fiction, but something that feels like I’m taking you along on some stories as I meet interesting scientists and learn about what they’re doing and go out in the field and watch whales.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: Cool. And what do you hope will change as a result of your book?

Nora Nickum: I hope that more people—both within the Pacific Northwest and outside the Pacific Northwest—will get to know these whales and understand how they’re important to the ecosystem and want to do things to help and find things that feel doable. Whether that’s making a phone call to a legislator or realizing maybe better not to wash your car in your driveway, take it to a car wash. Or looking up Seafood Watch, and how to get sustainable seafood, or doing a show and tell in school about these orcas and helping other kids in the class learn about them. And I hope people outside the Pacific Northwest will also get to know these amazing whales that we have here and feel a connection, even if they’re not nearby.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: Great. And Nora, what is next for you now?

Nora Nickum: I’m going to keep doing my Seattle Aquarium work, speaking out for policies to help these whales federally and at the state level. And I am working on additional books—some picture books coming out in the next couple of years and hopefully more middle grade in the future.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: Great. Well, we’ll look forward to those.

Nora Nickum: Thank you.

Laura (Blackmore) Bradstreet: Nora, I really appreciate you taking the time to chat with me today. Thank you so much for sharing your insights with me and thank you for the work that you do.

Nora Nickum: My pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Superpod is available in libraries and bookstores around the region, as well as through online retailers.

June is Orca Action Month. For Orca Action Month, Nora and Rein Attemann, Puget Sound campaign manager for Washington Conservation Action, presented on Southern Resident orca biology, threats to their survival, and ways we can support orca recovery, including specific actions boaters can take to help orcas. You can find events throughout June on the Orca Action Month website.