The Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge encompasses more than 4,500 acres around the Nisqually River Delta, where the Nisqually River, fed by glacial meltwater from the slopes of Mount Rainier, flows into South Puget Sound. The refuge contains the estuarine areas where the Nisqually River and McAllister Creek meet Puget Sound, saltwater and freshwater marshes, grasslands, mudflats, and forests. These habitats support salmon species and forage fish; waterfowl, songbirds, raptors, and shorebirds; snakes, newts, and frogs; and mammals like beavers, coyotes, deer, otters, and minks.

Easily accessible from Seattle, Tacoma, and Olympia, the refuge’s varied and beautiful landscape and abundant wildlife viewing opportunities draw more than 200,000 visitors to the refuge each year, including about 10,000 students. Among those visitors are hundreds of people who come to the refuge to hunt geese, ducks, and other waterfowl during the fall and winter hunting seasons.

Not everyone knows that National Wildlife Refuges allow both hunting and fishing within their grounds, but both those activities are key for the refuge system. Glynnis Nakai, refuge manager for the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge, explained that there are six priority public uses on refuges. “The National Wildlife Refuge System Improvement Act of 1997 identified priority wildlife-dependent uses, which are hunting, fishing, wildlife observation, wildlife and landscape photography, environmental education, and interpretation.”

During the 2020-2021 season, the refuge expanded the area where hunting is permitted, opening more than 1,100 acres of waters and tideland for waterfowl hunting. Nakai explained that the expansion was part of an initiative to attract more hunters to the refuge from surrounding areas. “Hunting is like a cultural activity,” said Nakai. “In the sense that there are a number of families that grew up hunting and it’s passed down from generation to generation. That’s part of the groundwork as to why we provide waterfowl hunting on the refuge.”

Why hunting and fishing are important for refuges

President Theodore Roosevelt created what would become the first national wildlife refuge in 1903, when by executive order, he named Pelican Island—a mangrove island in Florida where brown pelicans and other birds nested—a federal bird reservation. Later refuges were created by additional executive orders, land purchases, or legislative action by Congress.

In 1924 Congress created one such refuge, the Upper Mississippi River Wildlife and Fish Refuge, with the condition that hunting be permitted within the refuge area. Many of the early refuges that allowed hunting did so because hunting had been a traditional activity in the area before the creation of the refuge. Later, in 1934, the passage of the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act required waterfowl hunters to buy a duck stamp and established a new source of revenue for acquiring refuge lands. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, funds from the duck stamps have helped conserve almost six million acres of habitat since 1934.

Hunting on the refuges has gradually grown in popularity since the 1930s, and with later increases in the price of duck stamps, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agreed to open up more refuge acreage to hunting. Refuges contain habitat that supports healthy wildlife populations, and these populations often produce harvestable surpluses, as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service states. Hunting on refuges helps manage wildlife populations, and managers regulate the harvesting of wildlife to ensure a balance between population levels and habitat. According to U.S. Fish and Wildlife, the decision to permit hunting on wildlife refuges includes considerations of biological soundness, economic feasibility, effects on refuge programs, and public demand.

Hunting on the refuges supports conservation through both duck stamps and revenue from the excise tax established by the Pittman-Robertson Act, which helps fund wildlife conservation projects, hunter education, and recreation access. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service states that hunters and anglers have contributed more than $14 billion to conservation through the Pittman-Robertson Act.

“Sportsmen and sportswomen have been the system’s earliest champions, its strongest advocates, and its most generous contributors; no doubt they will continue to have a central role in its future.”

“National Wildlife Refuges: A Hunting and Fishing Perspective,” a report from the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership and other organizations, discusses how hunters and anglers have been key contributors to the success of the National Wildlife Refuge system. “Sportsmen and sportswomen have been the system’s earliest champions, its strongest advocates, and its most generous contributors; no doubt they will continue to have a central role in its future.”

The impact of hunting and fishing extends beyond the borders of refuge areas as well. As “National Wildlife Refuges: A Hunting and Fishing Perspective” notes, “… a 2020 Bureau of Economic Analysis report that found the economic output of outdoor recreation at $788 billion, exceeding more traditional sectors such as mining, utilities, and farming and ranching…These benefits also have a strong local impact: a 2016 study, for example, showed hunters in Montana spent nearly $100 million in the state, contributing to gas stations, sporting goods stores, and small-town hotels and restaurants.”

History of Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge and the restoration of the delta

The refuge lies within the traditional territory of the Nisqually Indian Tribe, who lived in villages throughout the river basin for thousands of years before the arrival of white settlers. After the Nisqually Indian Tribe, Puyallup Tribe, Squaxin Island Tribe, and other South Puget Sound tribes ceded their lands to the U.S. government through the Treaty of Medicine Creek in 1854, both the timber industry and agriculture transformed the land that would later become the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge.

In 1914, Alson Brown, a lawyer from Seattle, purchased more than 2,000 acres of land close by the Nisqually River Delta and built a long dike to transform the estuary into farmable fields.

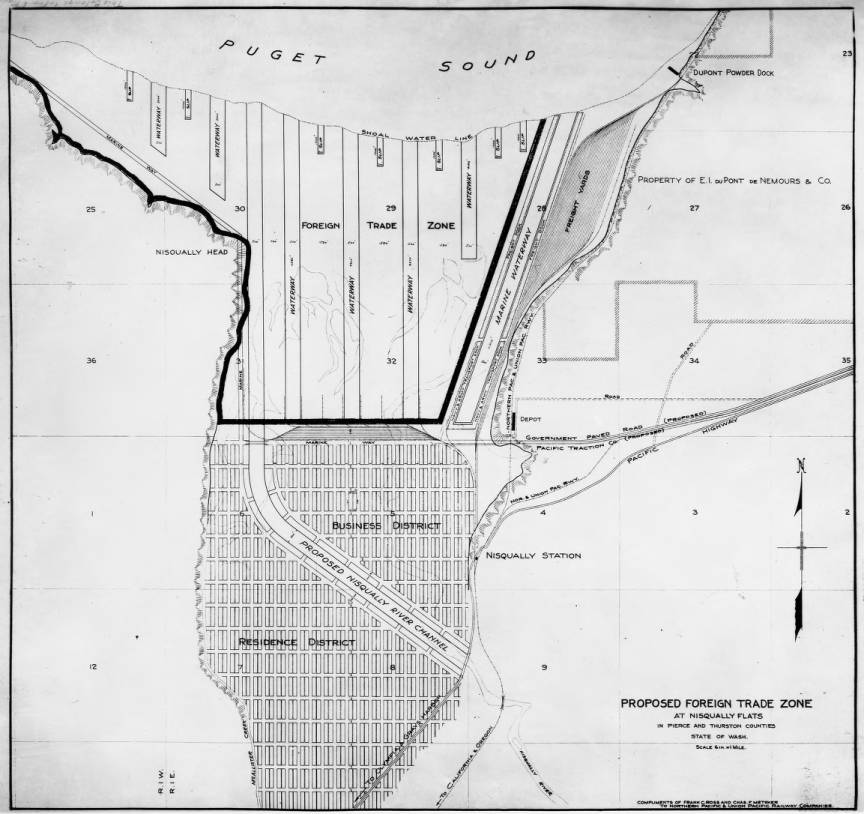

Later, from the 1940s through the 1960s, the Ports of Tacoma and Olympia proposed a new, deep-water port be established at the Nisqually River Delta to accommodate the larger and heavier ships developed for maritime trade.

The ports’ proposal gained momentum in 1965, but “met a solid wall of opposition,” as Mike Layton wrote in the August 26, 1965 edition of the Daily Olympian (precursor of the Olympian). The Nisqually Indian Tribe, the former Washington State Department of Game (now Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife), landowners, hunters and anglers, and local environmental advocates strongly opposed the plan to develop the area.

Thanks to the persistent efforts of those groups and community members, the U.S. Department of the Interior purchased 1,295 acres of the delta in 1974 to establish the refuge. (Read more about the history of the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge in this essay.)

1974 was also the year of the Boldt decision, United States v. Washington, which reaffirmed the treaty rights of Washington tribes and established tribes as co-managers of salmon and other fisheries with the state. The Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge is named after Billy Frank Jr. (1931–2014), member of the Nisqually Indian Tribe, treaty rights activist, and champion for salmon recovery, whose work with tribal leaders paved the way for the Boldt decision.

Christopher Ellings, salmon recovery program manager with the Nisqually Indian Tribe’s Natural Resources Department, explained that, following the Boldt decision, the Nisqually Indian Tribe, as co-managers, started to look closely at the Nisqually watershed and the salmon habitat in the river. “It was Billy Frank Jr., and then he hired my boss, David Troutt,” he said. “They started to hammer down on what needed to happen in the watershed in order to recover salmon and ensure that the tribe could continue to exercise this treaty right that was challenged and fought for.”

Starting in 1996, the Nisqually Indian Tribe worked with Ken Braget, the owner of a farm that occupied the banks of the Nisqually River, to start on habitat restoration. According to Ellings, the projects were small in scale at first, but fish were quick to occupy the restored habitat. Braget sold his farmland to the tribe in 2000 and continued to live on the farm, and the restoration work progressed quickly after that.

Ellings said that the tribe’s restoration projects in 2002 and 2006 were bigger in scope and showed they were on the right path. “We found that when elevations are correct that native salt marsh will come in quickly and that the fish would immediately access these areas,” he said. So these first projects—including one in 2006, I believe, that was a 100 acres—really set the stage for building the justification for doing the larger project on the refuge itself.”

As Ellings tells it, after the 1996 Nisqually River flood overran the refuge’s dikes and inundated some areas, Jean Takekawa, former manager of the refuge, sought funding to assess the feasibility of removing the dikes and restoring the delta. Takekawa collaborated with the Nisqually Indian Tribe on research on the effects of the early restoration projects and the significance of the delta as salmon habitat.

“Over 25 percent of the tagged hatchery Chinook we caught [as juveniles in the Nisqually River estuary] were from outside the Nisqually,” Ellings said. “And we were able to use this information to show that this was a regionally significant project in the restoration of the greater Puget Sound system.”

With these findings and the momentum from the earlier restoration projects, a group of partners that included the Nisqually Indian Tribe, the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, and Ducks Unlimited, launched the Nisqually estuary restoration project, the largest estuarine habitat restoration project in the Pacific Northwest.

The project secured public and private funds, including more than $1.8 million from the Puget Sound Acquisition and Restoration fund—co-administered by the Puget Sound Partnership and the Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office—pooled together by different watershed groups that contributed to the project; federal salmon project funding; and private funding raised by Ducks Unlimited.

Over the course of two years, from 2008 to 2010, the Nisqually estuary restoration project removed six miles of dikes and roads to restore more than 750 acres of estuary. The project cleared 1,000 feet of tidal channels and constructed another 2,000 feet of tidal channels; constructed a 1.8 mile setback dike; removed 5,000 cubic yards of riprap (rock armoring) from the Nisqually River and the restored estuary; planted more than 10,000 trees and shrubs on the setback dike and along the river; and added woody debris to enhance the salmon habitat in the restored estuary.

Before the restoration, the hard border of the dike ran in a loop around the outer parts of the refuge, inhibiting the natural meandering of McAllister Creek and Nisqually River and the exchange of water between the creek, the river, and Puget Sound. After the restoration, a thousand branching channels run through the tidal marsh and throughout the refuge, providing important habitat for Chinook salmon, chum salmon, steelhead, and a variety of other fish and wildlife.

Ellings said that in the years since the restoration, the monitoring and research has shown the changes to the delta have had beneficial effects for many different species, but especially for juvenile salmon. “From a salmon perspective, the work we’ve done to look at how Chinook salmon in particular utilize the restoration projects, it’s been very positive,” he said. “There’s a ton of habitat value—they’re getting a lot of food, staying there a long time, and growing really fast. And we have no doubts that we’ll start to see response by the adult salmon as the habitat gets better.”

The expansion of the tidal marshland also affected the number and type of birds that visited or inhabited the refuge, and the composition of waterfowl at the refuge has changed—Ellings said that there are more wigeon and estuarine waterfowl now than before. This change, in addition to Takekawa’s post-restoration decision to open refuge lands to hunting that were adjacent to Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife hunting lands, has created a large stretch of accessible and productive hunting land at the refuge.

Greg Sullivan, a hunter who’s come to Nisqually about a dozen times to hunt, explained that he likes the hunting at the refuge because it offers more than just mallards, snow geese, and teal ducks. “For example, there’s a group of at least six eagles in this area that are always cool to see,” he said “There’s a lot of marine wildlife and a good variety of waterfowl. I love that, no matter what, every time I come here, I’m going to see something interesting.”

Thanks to the following for their contributions to this article: Glynnis Nakai, Christopher Ellings, Michael O’Casey, Randall Williams, Eileen Price, Loren Wright, Cody Raffensberger, Tyler Klump, and Greg Sullivan.