The Olympia oyster, Ostrea lurida, is the only oyster native to Washington. Its historical range stretches from the coasts of British Columbia down to Southern California. Before the arrival of white settlers in Washington, there may have been 20,000 acres of Olympia oysters living throughout the bays and inlets of Puget Sound.

Before the 1800s, Olympia oysters were an important food source for tribes in the Puget Sound region. David Brownell, former tribal historic preservation officer for the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, said that Olympia oysters at the head of Sequim Bay were a sustainable resource for the tribe for at least a thousand years. Brownell explained that during excavations near the tribe’s administrative building, they found shell middens (piles of discarded shells) from 970 and 1,100 years ago that included a high proportion of Olympia oyster shells.

“Native species, especially foundation species like oysters, can help to support the native biodiversity of a system…”

— April Ridlon

Now, Olympia oysters are nowhere near as plentiful as they once were. According to the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW), Olympia oysters can mostly be found in their historic range throughout Puget Sound, but there are a lot fewer of them—probably five percent or less of their natural bed habitat remains. “Less than four percent of historic core populations was the estimate in 2010,” said Betsy Peabody, executive director of the Puget Sound Restoration Fund.

Starting in the 1850s, commercial harvest of Olympia oysters drove depletion of the wild stocks of Olympias. Later, in the twentieth century, pollution from pulp mills, the introduction of non-native predators and pests related to the cultivation of Pacific oysters from Japan, and habitat loss all contributed to the reduction of Olympia oyster populations in Puget Sound.

Olympia oysters are an important part of the Puget Sound ecosystem, not only for the ecological benefits they provide, but also in their role as a native species. Olympia oyster beds provide complex habitat for fish and invertebrate species and improve water quality through their filter feeding.

Olympia oysters also contribute to the native biodiversity of the region. “Native species, especially foundation species like oysters, can help to support the native biodiversity of a system,” said April Ridlon, lead for the Native Olympia Oyster Collaborative and SNAPP Postdoctoral Scholar at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis. “Restored populations of native oysters provide habitat for many native marine organisms, and are prey for others, such as shorebirds.” Ridlon explained that some studies suggest that Olympia oysters may also be more resilient to certain climate change effects than the introduced oyster species that are now grown commercially, and that more research into this is urgently needed.

To preserve this important species, WDFW in 1998 developed the Olympia Oyster Stock Rebuilding Plan, which laid out key actions for Olympia oyster restoration. The plan outlined priorities for population inventories, natural restoration, site selection criteria, water quality improvement, and habitat protection.

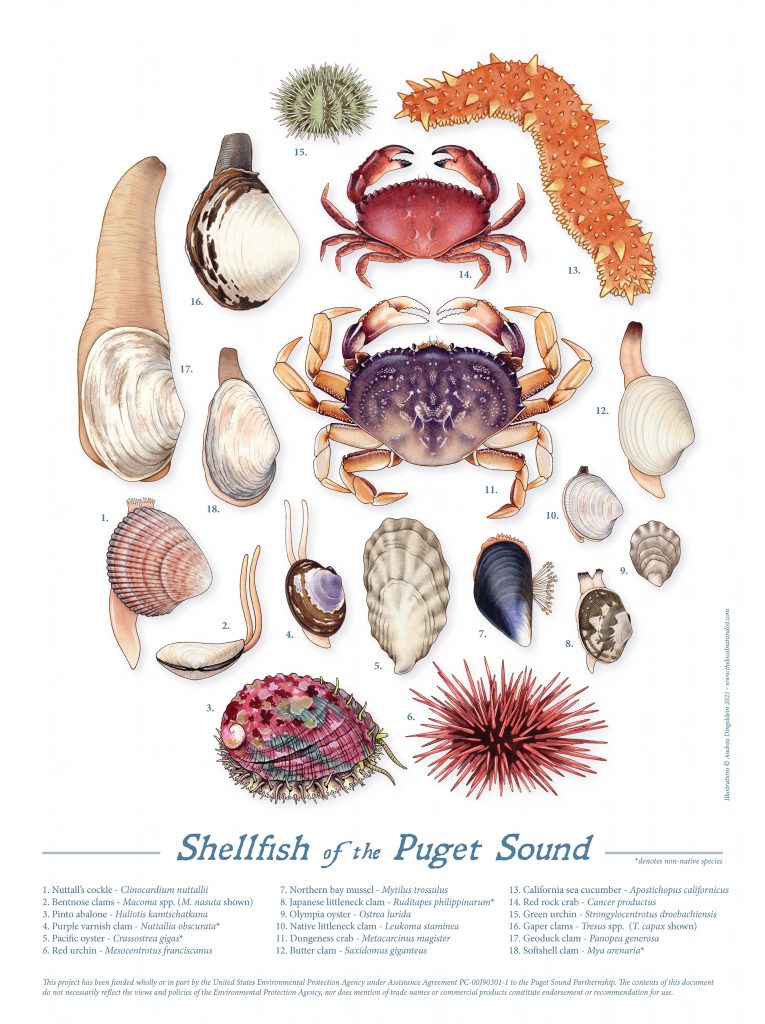

Puget Sound Restoration Fund, in cooperation with many partners, including tribes, federal and state agencies, local governments, foundations, and businesses, has used WDFW’s plan as a blueprint for Olympia oyster restoration efforts in Puget Sound. In 2010, Puget Sound Restoration Fund set a goal of restoring 100 acres of Olympia oysters by 2020. “In October 2020, we just managed to cross the finish line for that,” Peabody said. “With a 15-acre project at the head of Liberty Bay, near the city of Poulsbo.”

Restoration work has proceeded carefully over the last couple decades, and there’s a lot of optimism within the recovery community that Olympia oysters can once again thrive in Puget Sound. “These restoration areas are doing well,” said Neil Harrington, environmental biologist with the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe. “These mudflats where we might’ve seen very scattered Olympias now have tens of thousands of Olympia oysters that are spawning naturally.”

Thanks to the following for their contributions to the video:

- Betsy Peabody, Puget Sound Restoration Fund

- Neil Harrington, Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe

- Rebecca Erickson, City of Poulsbo

- Frank Curtin, Natural Resources Conservation Service

- April Ridlon, Native Olympia Oyster Collaborative and National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis

- David Brownell, Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe

- Paul Dinnel, Skagit Marine Resources Committee

- Julie Barber, Swinomish Indian Tribal Community

- Brady Blake, Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife

- Shina Wysocki, Chelsea Farms

- Jeff Dickison, Squaxin Island Tribe

- Eric Sparkman, Squaxin Island Tribe

- Brian McTeague, Squaxin Island Tribe

- Candace Penn, Squaxin Island Tribe

- Leila Whitener, Squaxin Island Tribe

Related stories from Northwest Treaty Tribes

Squaxin Island continues work to reestablish Olympia oyster population

Tribes, shellfish growers and partners support Olympia oyster restoration in Hood Canal